as the father of a friend of mine aged into his nineties, slowly shifting from vibrant and cheeky with well-fitting slacks and expensive shoes to pushing a walker in comfy flannel, grumpily yelling at people to speak up, she took some time to get prepared. before he needed it, she installed a safety bar and rubber no-slip pads in his bathtub, added his name to a list for an occasional personal support worker, and discussed his end-of-life wishes. and when he was diagnosed with cancer — and opted not to get treatment — she embraced his decision with grace, feeling confident that, whatever happened, she was ready.

after all, she lived right across the street from him made it easy to pop in often and if he needed her urgently, she could be at his side in minutes. her kids were teenagers and helped in their grandfather’s care, dropping groceries off, reading the newspaper to him, and even making fruity smoothies when he could no longer chew.

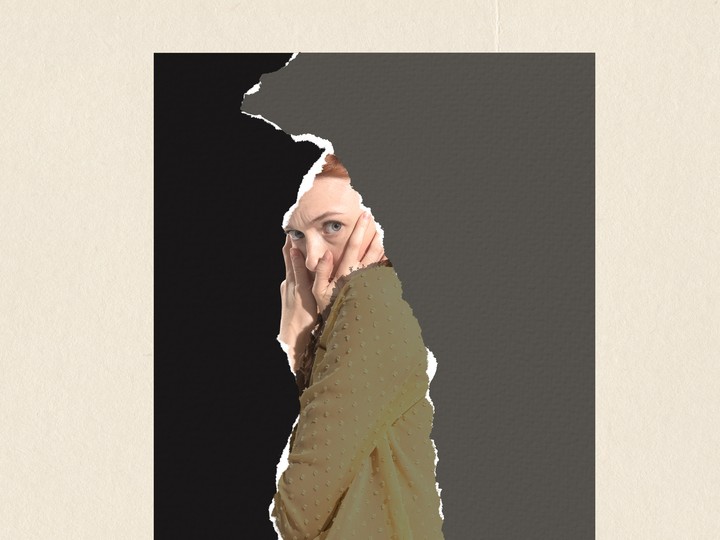

she began to describe her caregiving role as “traumatizing”

everyone in our friend group lauded her efforts to help her dad — though it wasn’t hard to spot the dents that began to appear in her super-caregiver armour as he became more sick. over several months, trouble sleeping and depression took a toll on her, she admitted to not thinking of everything, like the grief, and she began to refer to the whole experience as “trauma,” and “traumatizing” — always apologizing afterwards, guiltily tripping over her words as she reassured everyone how much she loved her dad.

5 minute read

5 minute read