westover: mental health lessons from my father's battle with als

i assumed he would get some medication for his understandable depression and anxiety. but that kind of care wasn’t on the roster – not for the patient, and not for my mom, the caregiver.

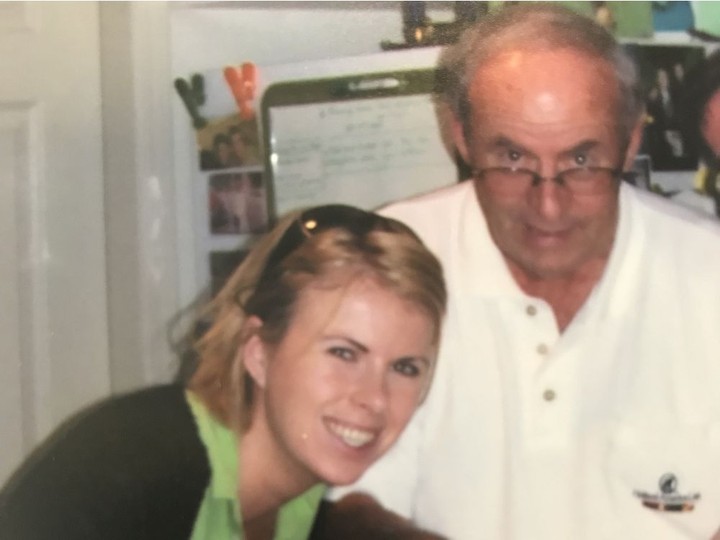

jim westover, at right, with his wife joanne and daughter suzanne. suzanne was a late 'surprise.'

jpg

by: suzanne westoverthere are few acronyms in the english language more loaded and paralyzing than als. my father was given this diagnosis, like a punch to the gut, in his 83rd year.until then, he was living a dream retirement. his sunset years had been spent on the golf green, or watching the waves from the crow’s nest of the holland america line cruises he loved. he and my mother were vital, vivacious. my friends gasped at the revelation of their chronological ages.i was my parents’ late-in-life surprise – an unexpected biological child after years of infertility and two adopted sons. my father, i think, never quite got over the miracle. at first a reticent third-time parent, he soon concluded that having a daughter was the icing on life’s cake. he lit up when i walked in the room. proud didn’t begin to cover it. i took it for granted that i would always have this special, almost super-human ability. my very existence was enough to make him happy.when he became ill with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, nothing could make him happy. i’m ashamed to say my ego took a blow. the light in his eyes went out, and for the seven months he lived with the disease, it only ever flickered again once or twice. als isn’t a ‘journey.’ it’s more like a road trip from hell, punctuated by reverse milestones.as a society, we laud those who face death with bravery. we celebrate people who are able to look their own mortality in the eye with seeming equanimity. we hear about people writing letters to their loved ones to be opened upon their death, a life-affirming postscript, a soothing balm to those left behind. my dad didn’t write any letters. he didn’t look back on his many achievements and heave a satisfied sigh at his approaching end. his reaction was all too human: he was angry, he was indignant and he was terrified.als is an awful disease. it robs people of their abilities, their independence and their dignity, a nickel at a time. als isn’t a “journey.” it’s more like a road trip from hell, punctuated by reverse milestones. there are the big ones: the last vacation, the last drive in the car. and there are small, intimate robberies too: the final solitary shower, the last unassisted footsteps.my dad had a dry sense of humour, but his outlook could veer towards dark. his middle name was maurice, but many years ago he got a voting card addressed to james morose. it was a running joke between my mother and me. dad didn’t find it funny. we tried to get him to laugh, or smile in those agonizing weeks of rapid decline. we reminded him of that card. we got a flicker. it was something.

advertisement

when my dad was referred to the als clinic after his diagnosis, i clapped my hands. “look mom,” i said, trolling the website. “he’s going to be seen first by a psychiatrist!” i was thrilled. i thought, finally a “holistic” approach. i assumed he would get some medication for his depression and anxiety. they get it. they understand that no one could be given this particular kind of news, living everyday with diminishing returns, without needing mental health support.my dad was fiercely competitive, right up until the end. he was frustrated when he could no longer beat his six-year-old granddaughter at beanbag toss. pretty soon, he couldn’t spin the wheel in a game of snakes and ladders. then, he couldn’t lift his arm to give her a hug. the biggest loss of all was left unspoken: he would never see her grow up. who wouldn’t be depressed in the face of this reality? but when my mom returned with my father from the clinic, i felt ashamed by my own ignorance.he didn’t see a psychiatrist. mental health isn’t on the roster – not for the patient, not for my mom, the caregiver. he saw a physiatrist. my mind played tricks on me. i hadn’t read the list of clinicians and practitioners carefully enough. his first encounter was with a doctor who specializes in rehabilitating people with injuries related to neurological function.there would be no rehabilitation for my dad. but what there could be – and should be – is a frank discussion about how being saddled with a relentless, untreatable, degenerative disease wreaks havoc with every aspect of one’s health. then, once we’ve had that conversation, we need to have the same one – this time, with the needs of the caregiver at the fore.i believe my dad’s final chapter could have been less fraught, if only for the provision of the right combination of psychological support. my mom enlisted the ear of a kind social worker. my father didn’t want to expend his limited energy making small talk with a stranger. he preferred to save his breath to exhort his children not to sell his model planes for a song, and to remind us where his rolled coins were hidden. perhaps, had he been given the opportunity early in his diagnosis, the anti-anxiety medication he was prescribed by his wonderful palliative care doctor would have eased his mental distress at the onset of the disease.

advertisement

just as lung cancer is linked to smoking, physical and mental illnesses are correlated. yet, the barrage of specialists my father saw didn’t include anyone trained in mental health.my father clung to what independence he could scrabble, right until the end. he used his thumbprint on his iphone to check his banking, he watched videos of his granddaughter as she learned to “fall down properly” on skates, and he was able to muster the will to tell me, on the morning of the day he died, that i’d been a wonderful daughter.if als is a curse, for my father it came with one gift: a peaceful death. he slipped away in his sleep, free from the ravages of his disease, including the depression and anxiety that were as real, and as painful, as the atrophying muscles in his arms and legs.on his very last day, he managed to ask, “how long do i have?” i told him i didn’t think it would be too long now. he nodded, and he almost smiled. almost. this was james morose, after all.it seemed to me he was, finally, okay with that.writer suzanne westover lives in ottawa with her husband and daughter.

5 minute read

5 minute read