'a lifelong challenge': living with a chronic blood cancer like cml changes everything

while chronic myeloid leukemia is no longer a death sentence for most patients, people like advocates amber noden and theresa harvey say that the side effects of medication have had huge impacts on their quality of life.

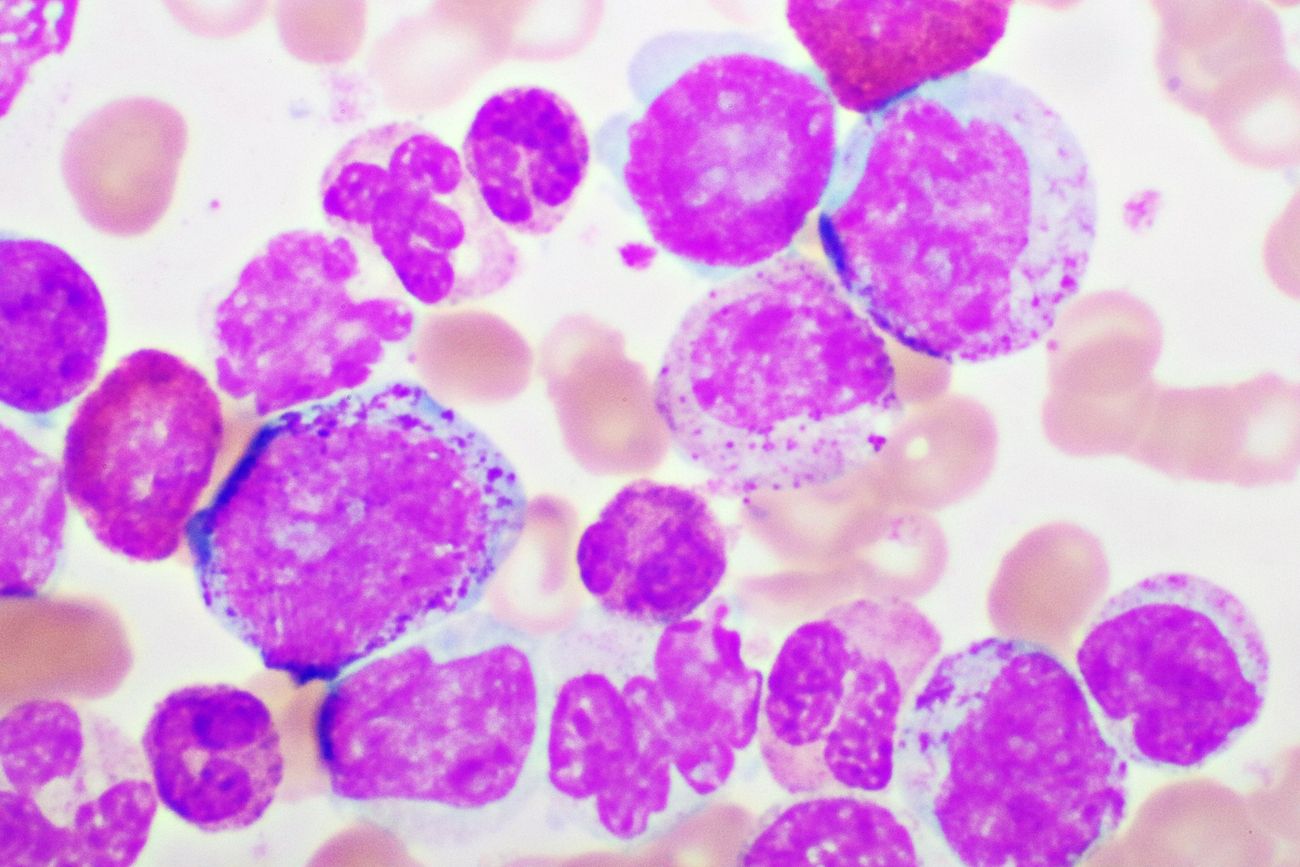

leukemia: do you know the signs?

leukemia occurs most often in adults after the age of 55, but it is also the most common cancer diagnosed in children younger than 15.

acute promyelocytic leukemia: 'i was just so desperate to hold on to life'

when michelle burleigh was diagnosed with acute promyelocytic leukemia, she was told that had she waited a day longer, she would have likely died from a brain bleed. today, she urges others to follow their gut, ask questions and don't let your concerns be dismissed.

7 minute read

7 minute read