how and why canada's car-t cancer network was built

“we had to come up with a strategy that made sense for canada and would work here."

gatineau's stefany dupont with her hematologist, dr. jill fulcher, who helped dupont enroll in a u.s. clinical trial using cutting edge car-t therapy after her leukemia returned for a second time in february 2017.

the ottawa hospital

/

jacob fergus/the ottawa hospital

gatineau’s stefany dupont was a few months into a new job with global affairs canada when she started to feel run down.it was february 2017.a recent university of ottawa graduate, dupont had faced off twice before with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, a cancer of the blood and bone marrow, and she worried her familiar symptoms — fatigue, shortness of breath — spelled more trouble. that fear was confirmed days later by doctors, who told her the cancer had returned.“honestly, i thought there wasn’t anything they could do,” she remembers.dupont was first diagnosed with leukemia at 13, and went through two and a half years of chemotherapy. five years later, she suffered a relapse and endured more chemo in preparation for a bone marrow transplant that gave her new, blood-producing stem cells.with a second relapse, at age 22, her options were drastically limited. at the time, an adult whose cancer returned so soon after a transplant faced a dire prognosis:the five-year survival rate was less than 10 per cent. one of dupont’s friends had died within months after such a relapse.“i didn’t have high hopes,” she says. “it was terrible.”in ottawa, doctors could only offer dupont palliative care. but her hematologist, dr. jill fulcher, and a colleague, dr. natasha kekre, a scientist at the ottawa hospital, knew of clinical trials in the united states where a novel cancer treatment known as car-t therapy was producing some remarkable results. they helped enrol dupont in one of the trials.first tested on leukemia patients in 2010, car-t therapy is designed to unleash the power of the immune system’s t cells against cancer.

advertisement

the treatment is at the leading edge of molecular biology and medical technology. as part of the therapy, a patient’s t cells — white blood cells that guard against foreign invaders — are genetically engineered to recognize and attack cancer cells, an internal threat. those cells, altered with the help of a virus, are multiplied in a lab and infused by the millions back into a patient.to prepare for the treatment, dupont had more chemo, but fell desperately ill with an infection. she spent two weeks on a ventilator and more time recovering before travelling to philadelphia for car-t therapy.“it was definitely the most stressful, fearful time of my life,” she says now.the children’s hospital of philadelphia was the site of some pioneering work in the field of car-t therapy. researchers there were part of a landmark study published in the new england journal of medicine in october 2014: it reported that 27 out of 30 young patients with advanced acute lymphoblastic leukemia had responded to car-t therapy and gone into remission.car-t worked a similar miracle on dupont’s leukemia. three months after the treatment, a bone marrow biopsy showed her disease was in full remission.dupont went on a trip to australia to celebrate.“i just wanted to do something for me, and to enjoy life,” she says.

advertisement

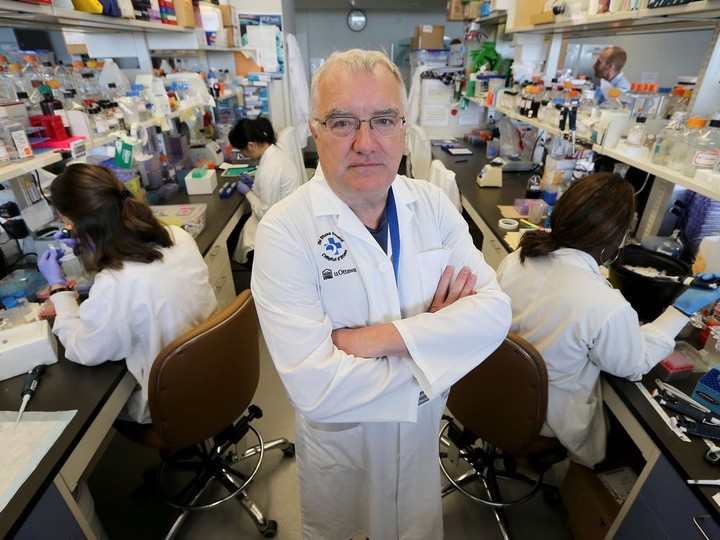

in the four years since then, car-t research has exploded. it is now one of the most studied — and most promising — avenues of cancer research and development.two commercial car-t therapies have been approved for use in canada: kymriah and yescarta are both used to treat aggressive blood cancers that have not responded to other treatments. the therapies are hugely expensive, costing hundreds of thousands of dollars for one-time treatments. (last year, the u.s. food and drug administration approved a third car-t therapy, tecartus, for the treatment of people with resistant mantle cell lymphoma.)new clinical trials are now testing the technology’s ability to engineer an immune system attack on the solid tumours that are a feature of advanced breast, prostate, pancreatic, lung and brain cancer.more than 150 clinical trialsinvolving car-t therapy are now recruiting in the u.s., offering hope to patients who previously had little.unfortunately, select few canadians have been able to take advantage of those innovative clinical trials. the therapies are fiercely expensive and complicated to administer, so only a handful of the u.s.-based clinical trials have canadian partners.it means most canadians with an untreatable cancer have to travel to the u.s. in search of a clinical trial.that situation has been a source of deep frustration for ottawa hospital hematologist dr. natasha kekre, an assistant professor at the university of ottawa. “for me, as a clinician, when my patients don’t get access to innovative care, i hate that,” she says.kekre is one of three ottawa scientists who have dedicated themselves to establishing a made-in-canada car-t research network to help address the problem.after years of work, a fledgling network is now in place: kekre is lead investigator in the first clinical trial with canadian-made car-t cells. the trial is currently recruiting patients in ottawa and vancouver.“because i do bone marrow transplants, i am unfortunately in the business of telling patients that they’re out of options and that they will succumb to their disease,” kekre says. “before car-t cells, i had that conversation many times. i still have that conversation, but it is less common now because at least i can say, ‘we have the potential for car-t cells.’”the drive to build a canadian car-t research network began at a halifax immunotherapy conference in june 2016, when kekre invited four more senior colleagues for drinks: dr. john bell and dr. harold atkins of ottawa, dr. brad nelson of victoria and dr. robert holt of vancouver.“natasha was a real butt-kicker: she was the one who got us organized,” remembers bell, a senior scientist at the ottawa hospital and one of the country’s leading immunotherapy researchers.kekre wanted to know if canadian scientists could manufacture their own car-t cells to jumpstart research and launch clinical trials in this country. bell says the question galvanized the group: “when we sat down, we said, ‘this is just craziness. we know how to do this. why aren’t we sharing our resources to do it?’”the problem was that none of the researchers focused exclusively on car-t cells; they all had established labs funded for other projects. car-t therapy was a different ball game.still, the scientists drew a game plan on a napkin. “we drafted out what we thought could happen — how we could mobilize using the resources we had in canada to make car-t cells here,” bell remembers.the scientists and their labs brought different strengths. ottawa had the ability to manufacture the virus required to deliver genetic material to a patient’s t cells; vancouver could make the genetic material to be inserted into t cells; while victoria had the expertise and infrastructure to manufacture the modified car-t cells.“we realized we have the people, we have the infrastructure, we just have to put the parts together to build a car-t network,” kekre says.says dr. harold atkins, a stem cell transplant specialist and researcher at the ottawa hospital: “it was like a puzzle where all the pieces fit.”the researchers collaborated on a 2,000-page funding proposal, but there were a series of hurdles to overcome. the scientists had to figure out how to co-ordinate their activity, how to deliver car-t clinical trials across the country and how to convince government officials the treatment was a justifiable expense inside the country’s cash-strapped public health-care system.“we had to come up with a strategy that made sense for canada and would work here,” bell says.

advertisement

an initial round of funding was secured in 2017 from biocanrx and the b.c. cancer foundation, with additional support from the ottawa hospital foundation. (ottawa-based biocanrx and its partners would ultimately invest more than $5 million in the project.)the research network the scientists built takes advantage of a “point-of-care” manufacturing process made possible by technological advances in the production of car-t cells. a german company, miltenyi biotec, has developed a portable machine that automates the production of the cells. previously, car-t cells could only be produced in large, specialized facilities because quality control was so critical. the clinimacs prodigy can make car-t cells in seven to 10 days almost anywhere.“i like to compare it to an easy-bake oven,” says atkins, an associate professor at the university of ottawa.right now, victoria is the only research facility capable of producing car-t cells. but ottawa scientists now have a prodigy machine and expect to be able to produce car-t cells later this year. similar capability is also being developed in toronto, winnipeg and vancouver. last month, the canadian foundation for innovation announced $5.2 million to extend the car-t network to kingston, hamilton, calgary and montreal.the canadian car-t network will not solve the problem of the therapy’s cost: it will remain expensive even if produced in this country. but the canadian network could help address the cost problem by establishing the value of automation in delivering car-t therapies and by improving car-t design.“i believe, in the long term, it could be very cost effective for our health-care system,” says bell.the first clinical trial with canadian-made car-t cells continues to recruit patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and non-hodgkin’s lymphoma who have not responded to other treatments. the trial is designed to establish that canadian-made car-t cells are safe and effective.cart-t therapy narrowly targets tumour cells, which usually makes it easier on patients than chemo or radiation since those treatments kill healthy cells alongside cancerous ones. even though it’s highly individualized, car-t does have potentially serious side effects, some of which can be life-threatening.it takes several months to recover from car-t therapy, during which time most patients will experience fatigue and a loss of appetite. more serious complications include confusion, headaches, seizures, and something called cytokine release syndrome, which can feel like a terrible flu, and can trigger a potentially deadly inflammatory condition. (it results from the massive release of proteins, cytokines, into the bloodstream by immune cells as they attack a target.)“it’s important to remember that car-t therapy is still very new and there can be serious side effects,” kekre says. “we need more research to learn about this therapy and make it work for even more people.”atkins says the difficulty canada has experienced in securing enough covid-19 vaccine demonstrates the importance of building a domestic car-t network. “this is going to be a very dynamic field for the next decade and we’re going to get some very interesting new treatments out of it,” he says. “people have so many ideas about how to make it better.”car-t is at the vanguard of the immunotherapy revolution, an approach that leverages the power of the immune system to destroy cancerous cells. the immune system does not easily recognize cancer as something to be destroyed because it’s not an invader: cancer evolves from defective cells already inside the body. cancerous cells also go through genetic changes to help them escape detection by t cells.car-t therapy re-engineers t cells so they can find and attack cancer. an inactive virus is used to insert genes into a patient’s t-cells to create artificial receptors — chimeric antigen receptors (cars) — on the surface of the cells. those receptors equip t cells with the ability to recognize a protein on the surface of tumour cells and to launch a chemical attack against them.the designer t cells infused during car-t therapy can stay on patrol in a patient for years to guard against a cancer’s return.they have so far protected stefany dupont. now 26, dupont has been in remission since her car-t therapy in philadelphia four years ago. she works for an international development organization in montreal, development and peace.she believes car-t and other immunotherapies hold immense potential, and she hopes they will one day replace chemotherapy and radiation as standard cancer treatments.“eventually, we should turn away from chemotherapy and radiation,” she says. “they work, but they’re very hard on your body. i don’t really know what my life expectancy is, but a lot of problems can come up later because of what i was exposed to.”dupont remains immensely grateful to doctors in ottawa and philadelphia for saving her life. she tries hard, she says, to be “normal” despite the psychological and physical challenges she faces.“it’s always going to be there and it affects me every day: my energy isn’t as high as other people. i have to be patient with myself a lot, take a lot naps and stuff like that. but, apart from that, i’m able to lead quite a normal life.”

9 minute read

9 minute read