rapid tests and other supports from feds going unused by provinces

according to the federal government's numbers, it has shipped more than 41 million rapid tests to the provinces, but just 1.7 million tests have actually been used

we apologize, but this video has failed to load.

try refreshing your browser, or

tap here to see other videos from our team.

tap here to see other videos from our team.

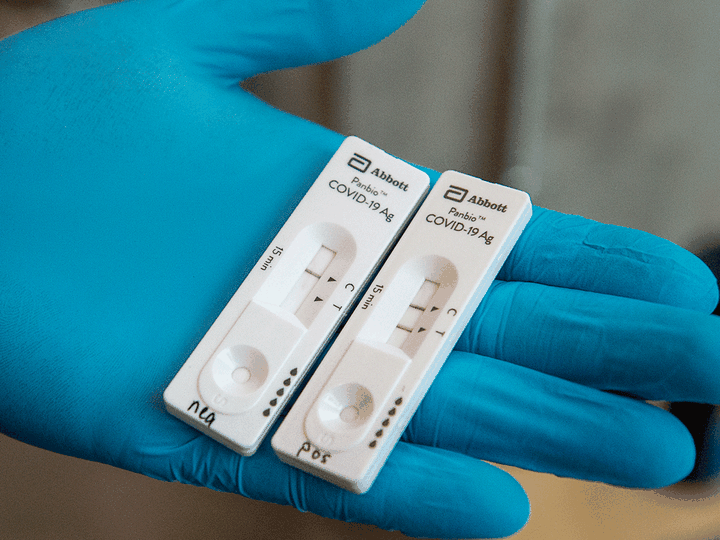

ottawa – as the country battles a crushing third wave of covid-19 that has filled hospitals and led to deaths and crippling economic lockdowns, provinces have declined to use several supports already available from the federal government, including a new drug treatment, rapid tests and help making contact tracing calls.on tuesday, prime minister justin trudeau announced military doctors and nurses would be sent to ontario and the government is also considering requests for more help in other parts of the country. but as this new help arrives, some of the previous supports the government has sent have gone unused.according to the federal government’s numbers, it has shipped more than 41 million rapid tests to the provinces, about a quarter of which have been pushed on to long-term care centres, workplaces and other settings, but just 1.7 million tests have actually been used to see if someone has covid-19.the full price of the multiple contracts the government signed for rapid tests has not been released, but a document obtained under an access to information request showed that for just one company’s rapid tests, the abbott panbio covid-19 antigen test, the government paid a total cost of $173 million. the government bought nearly 23 million units of the test and shipped them to provinces.those tests provide results in 15 minutes and have received the most use of any of the four the government purchased, but still only 1.5 million of the nearly 23 million have been actually used.trudeau said tuesday his government’s role is to ensure the supports are there, but he respects provinces’ decisions on how to use what the government provides.“our job as a federal government is to be there with supports that are needed and we’ve continued to do that. we respect provincial jurisdiction, provincial decision making, but every step of the way, we will work to fulfil the promises we have made to canadians.”trudeau said he would rather have supplies that aren’t used than not have them when canadians need them.alexandra hilkene, press secretary to ontario health minister christine elliott, said the province has pushed the tests out to workplaces and continue to work to put them in the right hands.“the government is in contact with dozens more interested companies to introduce testing at their work sites, and we continue to make steady progress in the distribution of rapid tests,” she said.tom mcmillan, a spokesperson for alberta health, said the initial health canada approval of rapid tests was narrow and provinces were restricted in how they could use them.“the rollout of rapid testing was delayed originally due to provinces adhering to the approved use of the tests licensed by health canada,” he said.mcmillan said the province can now use the test more widely and will be rolling more out to workplaces. on monday, the alberta government eased restrictions for the test further, by allowing them to be used by people who are not medical professionals.the federal government is also continuing to offer statistics canada operators to make contact tracing calls during the pandemic, helping to track people who may have been exposed to the virus to encourage them to isolate and get tested.several provinces have signed agreements with statistics canada to use the service, but even with cases at record highs the call centre has not been used to anywhere near its full capacity. the most recent data the agency has for the project shows it could have made nearly 120,000 contact tracing calls a week, but between april 11 and april 17, it made less than half of that at just over 50,000 calls.in november, after it received authorization from health canada, the government purchased 26,000 doses of bamlanivimab, at a cost of just over $40 million. the drug is a monoclonal antibody treatment administered intravenously that has shown positive results treating mild cases of covid-19, preventing them from becoming more serious cases.the drug was developed by vancouver company abcellera and manufactured with drug giant eli lilly. carl hansen, abcellera’s president and ceo, said there have been a few trial uses in b.c., but broadly provinces have failed to even consider using the drug.“there’s been a complete lack of initiative and leadership in getting therapy to patients,” he said.

advertisement

hansen is clear the drug is limited to people in the early stages of covid-19 and won’t help those already in icus. he also said it is not as effective against all new variants, particularly the p1 variant first identified in brazil.in the u.s., the fda has revoked its emergency authorization for the drug as a stand-alone treatment due to those variants, but is still approving the drug to be used in combination with another similar drug and there have been no reports of serious adverse events.hansen said the drug has shown strong results against original strains of covid and the u.k. variant that is widely circulating in ontario.“in ontario, if tomorrow you started doing infusions, every 50 infusions you did would save someone’s life, every eight to 10 infusions would save a hospital visit. it’s as simple as that,” he said.kerry williamson, a spokesperson for alberta health services, said the province has looked at the drug and is prepared to use it in a limited trial fashion, but a review of the current evidence left them unconvinced.“this decision to limit bamlanivimab use to the study is based on ahs’ review of the current evidence which notes further study is required to determine whether bamlanivimab offers benefit to patients with mild to moderate covid-19,” he said.williamson also said administering the drug would take away resources, because it must be done through an iv.“bamlanivimab requires intravenous administration, and any proposed use would require support from front-line medical staff in an outpatient care setting,” he said.hilkene, with the ontario government, said the province’s science table considered it, but was similarly not sure it was ready.“the current guideline summary from the science table notes that bamlanivimab is not recommended outside of clinical trials. the science table will continue to monitor new clinical information regarding bamlanivimab and update its recommendations accordingly,” she said.hansen said the new clinical trial information the company has conducted should end any doubts and he stressed it has little to no side effects. he said u.s. hospitals found a way to use the drug successfully, but provinces haven’t shown the same interest.“it’s not as though we tried and failed. we never even tried. there hasn’t been an effort to solve any of the logistic problems,” he said.he said while canada waits for more vaccine the drug could still be put to good use to help prevent mild covid cases from becoming severe.“in vaccines we have no supply, here we’ve got supply. we bought it, it is sitting on the shelf, it works and we cannot muster the effort to actually bring it to the patient.” he said. “it is an appalling failure of our system.”• email: rtumilty@postmedia.com | twitter: ryantumilty

5 minute read

5 minute read