the pandemic means more of us remember our dreams

if it seems you’re dreaming more frequently or more viv...

the covid-19 pandemic has disrupted sleep patterns, a state of affairs that doesn't bode well for our health. but it is also making people dream more vividly. and that's a good thing. photo illustration from shutterstock

kladyk

/

getty images/istockphoto

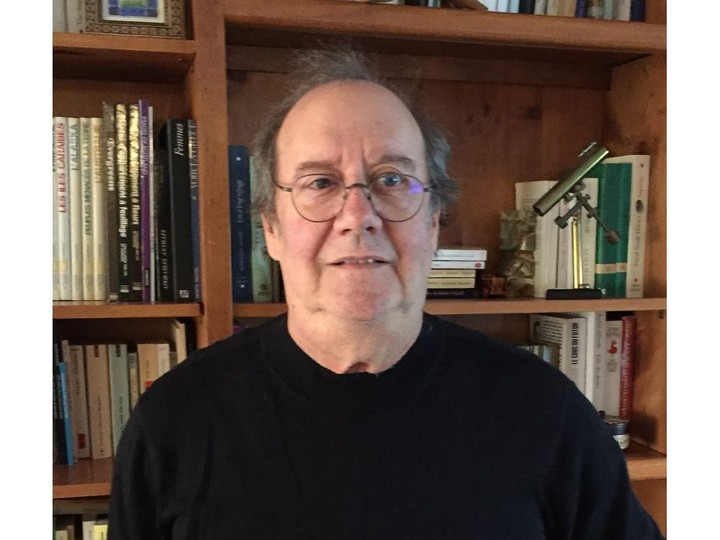

if it seems you’re dreaming more frequently or more vividly than usual, you’re not alone.the stress related to the pandemic means that sleep has become more fragmented, which means people are more likely to remember dreams.and because many people don’t have to get up to prepare to go to work, they’re sleeping later.the last cycle of rem sleep in the morning hours lasts longer and the sleeper wakes up immediately after, which is what makes these dreams so vivid, said dr. joseph de koninck, a professor emeritus of psychology at the university of ottawa who has studied sleep and dreams for five decades.the amygdala, the part of the brain that processes memory and emotions, is active during dreaming, while the centre that controls rational thought is in repose. few people read, write or count in their dreams, for example, said de koninck.“dreaming is open season for the mind. there are no restrictions in dreams. you can kill people, or be killed. fantastic things can happen. you can fly.”

typically, only about half of people remember their dreams. because sleep has become more fragmented, some people who don’t normally remember dreams are now recalling them. it has added up to an epidemic of dreaming, a phenomenon that has been reported around the world.a survey of sleep habits launched by canadian sleep scientists on april 3 has found that between 20 and 30 per cent of the approximately 2,300 respondents have reported that the intensity and frequency of bad dreams and nightmares has increased.“and for most of them, this is actually disrupting their sleep,” said dr. rebecca robillard, who leads clinical sleep research at the royal ottawa’s institute of mental health research.those who reported greater frequency and intensity of bad dreams or nightmares were more likely to be female, and to have higher stress, anxiety and depressive symptoms.the survey, which is still open, is aimed at taking the pulse of how people are coping and at assessing the psychological, social and financial impacts of the pandemic. “all of which interact with our sleep and dreams,” said robillard.

advertisement

dreams are fascinating because they have a function in themselves. they are not a repetition of conscious life, said de koninck.“dreams are never a replay of the day. usually, the only one who can make the connection is the dreamer, because dreams are distorted,” he said.one study, for example, showed that it was very difficult for independent judges to connect the events a person reported from their waking day with the content of their dreams.issues that bother you in the day, which may be subliminal, follow you into the night, said de koninck.“there’s tension, not necessarily conscious, that eats up a lot of your brain’s time. you might not notice it, but you’re trying to deal with it. everything you do now, even going to the grocery store, is quite stressful.”in the pandemic environment, the brain is constantly trying to process anxiety and uncertainty, he said.“your brain is like a computer. it’s like you have a computer virus that’s taking up space.”de koninck recently received a social sciences and humanities research council grant to further analyze a “bank of dreams” from 1,200 subjects ranging in age from 12 to 85 years old.many elderly people dream of things they did when they were adolescents. the intense emotions people had in that time resurface in their dreams for the rest of their lives, he said.some researchers have proposed that dreaming helps in the adaptation to stress.the “threat simulation theory” of dreaming posits that dreaming is an ancient biological defence mechanism used to help mentally prepare for a worst-case scenario, said de koninck. people asked to rate the stressful emotions in their own dreams often say that they cause less anxiety than an independent judge asked to rate the same dream.the sleep survey has found overall increases in stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms, as well as sleep difficulties during the pandemic, said robillard. but the nature and extent of those changes varied.on average, people have reported that they are taking longer to fall longer to fall asleep and their sleep was more broken up. others, especially those working from home, reported getting more sleep.“those who sleep less report poorer sleep quality, and also seem to be more stressed,” said robillard.dr. julie carrier, a psychology professor at the university of montreal and scientific director of canadian sleep and circadian network, said dreaming has received a lot of attention during the pandemic. but insomnia and other sleep disorders are an important issue.sleep scientists argue that restful slumber is a public health matter. sleep deprivation affects mood and motivation and results in bad decision-making. among other conditions, sleep disorders have been linked to obesity, type 2 diabetes, depression, and dementia.before the pandemic, about a quarter of canadians suffered from sleep disorders, said carrier. she believes this proportion will be higher — not just during the pandemic, but for months after.“the challenges, social and economic, will still be there,” said carrier.“frontline workers were already on atypical schedules. now they’re doing it under a great deal of stress. and they don’t have time to recuperate.”at the same time, many people working from home are juggling responsibilities, such as childcare, while working.“the message is that we have to make sleep a priority for health, here and now. it is a predictor of your cognitive and emotional life in the future. it’s an investment in your future health.”restful sleep is a biological necessity.a quarter of canadians were sleep-deprived before the pandemic. for many, the outbreak and the anxiety and stress it had brought has made it even harder to get a good night’s sleep.here are some tips from sleep researchers:— try to get to bed at your accustomed time instead of going to sleep later and waking up later.you can so this by standing in front of a window early in the morning, to keep your biological clock’s synchronization, said university of ottawa sleep researcher dr. joseph de koninck.— for those who have frequent bad dreams or nightmares, try not to worry too much, said dr. rebecca robillard, head scientist at the royal ottawa institute of mental health’s sleep research unit.“this is a normal reaction and may in fact be a sign that your brain is actively processing some of your daytime stress and tension,” she said. “this may be a helpful adaptive mechanism from the standpoint of emotional regulation.”— protect 30 minutes to an hour before bedtime to engage in relaxing and pleasant activities to progressively get in the right mind space before sleep, said robillard.

5 minute read

5 minute read