powered by:

valneva canada inc.

barreto: why covid-19 apps won't save canadians

the way forward must be for the government to meaningfully invest in the social determinants of health and avoid the false sense of security this technology may provide.

aug 11 2020

3 minute read

3 minute read

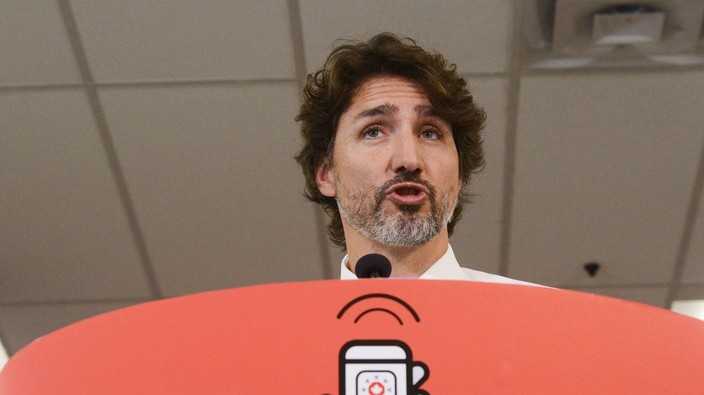

prime minister justin trudeau holds a press conference recently to tout the new app.

sean kilpatrick

/

the canadian press

canada has joined other countries in rolling out an app, covid alert, to help manage the covid-19 pandemic. in theory, this app would curb transmission by alerting people if they have been near someone who later tests positive. the disappointing truth to-date is that these apps don’t appear to have helped much, at least not on their own.

despite little evidence of the apps’ effectiveness, canada has nevertheless released its own, settling on a decentralized google-apple bluetooth framework that has appeased the concerns of many privacy commissioners and critics. however, focusing only on privacy, while certainly important, puts the cart before the horse, detracting from fundamental questions about whether an app is effective or necessary for optimal population health in the first place. the way forward must be for the government to meaningfully invest in the social determinants of health to curb covid-19 and avoid the false sense of security an app may provide.

first touted as contact tracing apps, they are now more accurately classified as “exposure notification apps.” contact tracing is a traditional public health practice indispensable to managing sexually transmitted infections and respiratory diseases such as tuberculosis. to streamline this process, the idea of an app performing some contact tracing functions rapidly spread. unfortunately, covid alert will leave out large swaths of the population, many of whom are more susceptible to contracting, transmitting, or dying from covid: people who are either elderly, incarcerated, homeless or low-income, as well as children.

advertisement

advertisement

the app operates on a multi-stage voluntary basis, with many possible points of user attrition, including whether it works on your model of smartphone — if you have one. a user needs to download the app, always carry their phone, opt to get tested, and opt to upload their positive test result. once another user receives a notification that they may have been exposed, they would then opt to self-isolate and get tested. for only the possibility of exposure, this is a demanding engagement cycle with no clear means to measure user follow-through or impact, particularly in populations already under financial and psychological stress.

any medical or public health intervention requires an understanding of the long history of institutional abuse and neglect of black and indigenous people in canada and why some populations tend to avoid engagement with the medical system until absolutely necessary. systemic barriers to good health have driven disproportionate rates of covid-19 amongst black, indigenous and communities of colour. these are some of the same groups suffering from racist police violence while simultaneously comprising many essential service industries. it would not be surprising if they resisted adopting a government app to track health. regardless of bluetooth’s better privacy protections, we know that trauma from institutional racism, discrimination or criminalization has an impact on marginalized communities’ engagement with public health.

advertisement

advertisement

while the voluntary covid alert is not enforced by the government, we must ensure new technologies are not enforced by employers or used as a means of discrimination, surveillance or coercion to return to work in potentially unsafe environments. rhetoric like “don’t worry, we have the app” fails to recognize the systemic barriers behind people not using it and places trust and responsibility in unproven technologies.

further, as dr. ruha benjamin highlights in her book race before technology , the politics and purpose of design matter. the stated intent of the collaboration between apple and google in designing this framework is to “accelerate the return of everyday life.” the return of everyday life, starkly illustrated by protests against white supremacy and police violence, is not something many people living under the heel of systemic racism want. the true intentions of an unusual collaboration between two tech behemoths, whose business models and human rights practices have been roundly criticized, must be interrogated.

virtually all population health concerns can be connected to inequitable access to social determinants of health that include adequate housing, income and food security. proven answers to ending the pandemic can be found here, not in proclaiming the promise of a shiny new app, touting its privacy features to distract from government responsibility to address the daily realities in people’s lives that facilitate covid-19 transmission.

advertisement

advertisement

public health approaches that exclude affected populations will never eradicate a disease, particularly when it comes to the ease of transmission of respiratory pathogens. in the words of scholar dr. safiya noble, an app won’t save us. we have to save ourselves. we already have the knowledge and tools to do it. we just need the political will.

daniella barreto holds an msc in epidemiology and is the digital activism coordinator at amnesty international canada.