moloughney uses the example of a high school with 1,500 students.“you may not need to close the entire facility if you think the risk is only to one cohort or two cohorts. those at highest risk would be in self-isolation and then we assess risk beyond that cohort and react accordingly.”the province has said that outbreak interventions should be “scaled, adaptable and measured.” among the factors to be considered: the number of cases; confidence in cohorting implementation; the number of cohorts affected; local epidemiology and the needs of vulnerable student populations.q: will class sizes be reduced?a: this is the biggest area of contention. last week, for example, toronto public health urged the toronto district school board to keep elementary class sizes smaller than normal.ottawa public health said it “supports having the number of students within a classroom to be as small as possible, in order to facilitate physical distancing, and to maintain distancing and limit the mixing of cohorts in common areas such as hallways and washrooms

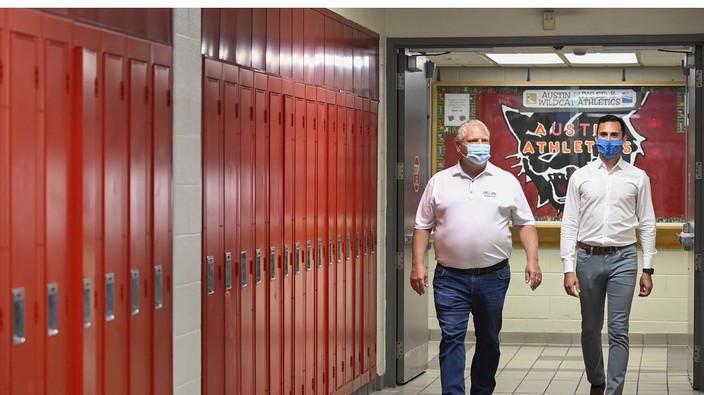

.” the province has insisted the measures it has already announced, including making masks mandatory for grade 4 and up, investing in more custodians, hand sanitizer and nurses, as well as more teachers in the hardest-hit jurisdictions, will help keep students safe.education minister stephen lecce also announced lats week that the province was spending $20 million on “robust testing of asymptomatic students, particularly in high school, where the risk is higher.” but no details have been released.“our plan is the best plan in the entire country,” premier doug ford said on friday, while at the same time acknowledging that things can change, and the plan has to be flexible.

q: how does everyone play a role in preventing outbreaks in schools — even those who don’t have school-aged children?

a: infection is a loop between the community, schools, then back to the community, said ashleigh tuite, an infectious disease epidemiologist and mathematical modeller at the university of toronto.

“if we have fewer cases in the community, there’s less chance we’ll introduce covid-19 into our schools, where we could see outbreaks,” she said.

“to use the whack-a-mole analogy, it’s easier to keep covid under control in schools if there are fewer moles to whack.”

q: what has happened in other jurisdictions?

a: israel has been cited as an example of how not to return to school.

schools in israel re-opened in late may. safety measures at the time included masks for children in grade 4 and higher, windows to be kept open and frequent hand washing.

but classes were large and physical distancing was a problem. as the weather got hotter, the israeli government allowed everyone to stop wearing masks for four days and closed the windows to allow air conditioning to keep temperatures down.

infections “quickly mushroomed into the largest outbreak in a school in israel, possibly the world,” said the new york times about what happened at gymnasia ha’ivrit high school in jerusalem.

“the virus rippled out to the students’ homes and then to other schools and neighbourhoods, ultimately infecting hundreds of students, teachers and relatives.”

all the students and staff were tested and had to wait in line for hours. teachers who taught multiple classes were hardest hit. some were hospitalized.

the israeli education ministry later shut down schools with even a single case, closing 240 schools and quarantining more than 22,520 teachers and students. re-opening schools was identified as a major contributor to a second wave of covid-19.

the school year in israel is scheduled to start on sept. 1. recommendations for the reopening have included creating cohorts of 10 to 15 students, staggering school schedules, online classes for some students, mandatory masks for older students and frequent sanitizing.

q: could what happened in israel happen in ontario?

a: it’s not outside the realm of possibility, said tuite. but she points out that there were some factors at play in israel that led to these outcomes.

“these were very large overcrowded classrooms. people weren’t wearing masks because there was a heatwave.”

even if schools are perfectly set up, positive cases will still appear, she said.

“if cases do get in, as they very likely will, what do you do to minimize it? schools have never been zero risk. there is a risk associated with every action.”

q: will ontario’s schools be safe in september?

a: there are both academic and social harms to children is schools stay closed, points out moloughney.

“we’re looking to make school as safe as possible. we’re reopening while we have covid (in the community) so the question becomes how to design and weigh reopening schools in a way to make it as safe as possible.”

9 minute read

9 minute read