what are hospitals doing to support bipoc communities?

“you can feel the tone change sometimes when you walk into a black patient’s room. because they know that you know.”

ellen odai alie from the ottawa hospital, civic campus. monday, jun. 7, 2021.

jpg

by: taylor blewetteight days after the murder of 46-year-old black man george floyd under the knee of a white minneapolis police officer, ottawa’s largest hospital joined individuals and institutions around the world in posting a plain black square on instagram.the ottawa hospital shared the uncaptioned image as a part of blackout tuesday, a social media movement intended by many to represent solidarity and reflection as anti-racism protests swept the globe in the wake of floyd’s killing, but which also generated condemnation as little more than virtue-signalling.for ellen alie, a black woman and corporate manager of breast imaging at the ottawa hospital (toh), the black square wasn’t enough.“toh is not just a health-care institution, we are a part of the community. and i felt that it was really important for us to say something,” alie told this newspaper in an interview.alie knew the hospital had been doing work related to diversity and inclusion, and wanted them to speak to that, but she also thought it important to highlight the gaps the organization had yet to bridge.she spoke up, and was met with “total support across the board,” including from then-hospital president and ceo jack kitts, as well as the hospital’s vice-presidents of communications and human resources.“everybody was just like — yes, we actually have to say something. we can’t just let this go,” said alie.so began the hospital’s healthy conversations series, which debuted last june with a series of live q&a videos and a panel discussion on racism in health care, with black toh staff members. all are still watchable today through the hospital’s website and facebook page.

advertisement

in her solo video, alie recounted an experience she had when she was a patient getting a procedure done at the hospital. the physician seeing alie explained the procedure might be painful, but because she’s black, “you have thicker skin and you don’t feel as much pain, so it won’t be as bad for you.”trying to decide what she was going to say or not say in response, and considering whether doing so might affect her care, alie said she didn’t hear half of what the doctor was telling her about the procedure.“you think about all the other people who walk through the doors of the ottawa hospital, and the patients who don’t have any experience in the health-care system, and how that kind of racism actually impacts the care that they receive, and impacts their outcomes.”the premise of the healthy conversations series was to have bold discussions, alie said — to feel uncomfortable, and not shy away.“i think these conversations have let people see that we’re willing to go there as an organization. we’re willing to have these tough conversations, as uncomfortable for some as it may be, because if you don’t put things out there, if you don’t see it, how will you be able to acknowledge it and do it?”on june 5, 2020, the day thousands gathered in downtown ottawa for an anti-racism protest and march honouring george floyd and other victims of police violence, four of the city’s local hospitals — queensway carleton, cheo, montfort, and bruyère — shared public statements that voiced solidarity with the protesters and denounced racism.last month, a year after floyd’s death, this newspaper interviewed representatives from each of those hospitals, as well as toh, to probe what they’ve been doing since those statements were released to combat racism in health care, support bipoc patients and staff, and reflect in their workforce the diversity of the community they serve.while gaps exist — among them, data about the racial or ethnic identities of their staff and their patients — local hospitals have acknowledged the status quo isn’t cutting it. in different ways and to different degrees, work is being done to offer more than just words to patients and staff for whom racism, systemic or otherwise, is not only a phenomenon to protest, but a reality to bear.that reality can have the harshest of consequences. just ask the family of joyce echaquan, a 37-year-old atikamekw woman who died in a quebec hospital after filming staff ridiculing her, and according to testimony at a recent coroner’s inquest, not having her condition taken seriously.inequity can also exist more quietly in hospitals, making itself known in the scarcity of non-white faces on leadership rosters, or in who gets how much pain medication.the causes may be complex, and responsibility is diffuse but there’s plenty of room for hospitals to move the needle.

advertisement

sharon nyangweso, founder and ceo of ottawa-based inclusion agency quakelab, has noticed a tendency in her work with clients that involves people wanting to “jump straight to a solution without having a clear understanding of what it is they’re solving for.”what this looks like, she explained, is the perceived need for things like anti-racism training or the hiring of more people of colour, but when asked what the problem is that this proposed solution is addressing, answers lack substance.on the other hand, if organizations take the time to identify specific challenges — for example, criminalizing indigenous people seeking health care with assumptions about drug use — and then consider how to solve for that challenge, “it becomes a lot more practical than saying, ‘what we need to do is train our nurses to not have unconscious bias,’” said nyangweso.the people this newspaper spoke to who are involved with equity, diversity and inclusion (edi) work at local hospitals did talk about efforts (past, planned or ongoing) to try to understand where their organization needs to improve, often through consultation with staff and communities outside of the hospital.at montfort, consulting firm kpmg has been retained to support the work of a grassroots hospital edi and anti-racism committee — established in the wake of the local anti-racism protest last june — on an action plan that includes documenting instances of systemic racism at montfort.a review of hospital policies and procedures, focus groups, and a voluntary staff survey involving self-identification as a member of a minority group and questions about working environment, training opportunities and the like are all part of this work.“we need to know what is going on, and we don’t want to be blind or blinded, because we know that we are in a society where there are some inequities,” said committee co-president ursula dika. “we are not exempt or we are not … discrimination-free, for sure, at montfort.”kpmg was expected to provide a report and recommendations in the coming weeks, which will feed back into the committee’s work.at queensway carleton, it was during recent strategic planning consultations that an employee said to greg hedgecoe, vice-president of people, performance improvement and diagnostic services: “you know, greg, when i’m at a leadership meeting, and i looked around the room, it’s not very colourful,” hedgecoe recalled.“that made me step back a little bit, (and say) ‘wow … you’re right.’ and get curious about why is that and what can we do about that.”that moment helped drive the implementation of a leadership bursary for diverse talent this year, said hedgecoe, created to try to support the advancement of employees belonging to equity-seeking groups into hospital management roles.in and of itself, representation doesn’t drive change. but paul bailey, executive director of the black health alliance, does think it’s important, especially when it comes to hospital leadership and management, as well as patient advisory bodies.“if you only have one or a limited number of experiences that are designing health care and designing health-care services and how we engage with patients, it’s designed with one lens,” said bailey. often, it’s a eurocentric view that may not recognize how others experience or understand health care.

advertisement

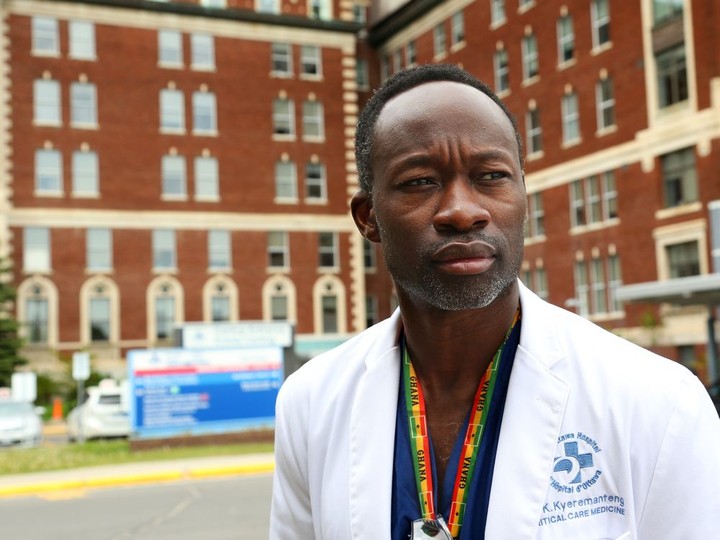

at the practitioner level, dr. kwadwo kyeremanteng has seen firsthand how access to a health-care provider whose background aligns with your own can affect a person’s care experience. he remembers an elderly patient of african heritage, nearing the end of their life, who had a reputation for being difficult to deal with.“i remember walking in the room, and because of our shared heritage … the patient’s eyes just lit up. they were so engaged, they opened up about what their concerns and their fears were.”as a black physician, one thing kyeremanteng feels he can offer to a black patient is the knowledge they’re less likely to be judged.“that doc that looks like me … he knows what it means to be a black patient, he knows what it means to be a black person, and what that carries.“you can feel the tone change sometimes when you walk into a black patient’s room. because they know that you know.”kyeremanteng, a critical and palliative care doctor at toh and montfort, said he’s still one of the few black physicians at any of the sites he’s ever worked at. he did note, however, that especially since the death of george floyd, there have been more efforts to address concerns around diversity and inclusion.at the moment, it’s impossible to say exactly how reflective ottawa hospitals are of the community they serve, because none of the five had been collecting data from staff about their race or ethnicity.that’s a problem, in bailey’s eyes.“not collecting data is an acknowledgement … for me at least, that it’s (not) a priority for these organizations or institutions. you can’t change what you don’t measure.”it’s something local hospitals are reckoning with now. queensway carleton, for instance, is planning a survey of employees and physicians, inviting them to voluntarily self-identify if they’re a member of an equity-seeking group, and asking questions around perceptions of inclusion and belonging. the information will be kept confidential, and used to help “pinpoint opportunities for improvement that we can address through targeted strategies.”hedgecoe said it was historically thought that if you had systems that were bias-free, then there would be diversity in the workforce.“the enlightened thinking now is – no, you need to do more than just ensure bias-free systems. you need to measure whether there’s a problem, track progress over time and ensure that we are equipping people with the skills to manage their own unconscious biases.”nyangweso, of quakelab, did sound a cautionary note about efforts to increase the staffing diversity of institutions — namely that new hires should not be the answer to structural problems.“if you haven’t cleaned house, you’re more or less bringing in these folks to just face the exact same harm that we’re saying exists in your institution,” she said. “that is not equitable, that is not justice, that is just … exacerbating existing harm.”the collection of race-based patient data is another area receiving increased attention as of late, fuelled in large part by the covid-19 pandemic and its disproportionate impact on racialized communities.many canadian health-care institutions don’t routinely collect data about race, an april 2020 report from the upstream lab at unity health toronto notes.meanwhile, research using data that is available in canada “has consistently documented that racial disparities in access to health care and overall health outcomes exist.”the report also notes that in this country, “preventable negative health outcomes are disproportionately seen in indigenous and black patients.”monitoring, reporting on, and improving care and outcomes for these and other racialized populations are why it’s important that race-based and other sociodemographic data be collected by hospitals, and across the health system, bailey explained.nyangweso also pointed out that “unfortunately, just because of the way the world is, the most marginalized people have an uphill battle when it comes to saying, ‘this is a thing that’s happening.’”in the absence of data, she explained, it’s easy to write off the accounts of individual patients as isolated incidents, or dismiss reported patterns of inequity, if there’s no hard proof to back them up.a lot harder to ignore is quantitative evidence, like that presented in an ottawa-led study published in may, showing indigenous patients had higher rates of post-surgical complications, such as infection and readmission to hospital, and were 30 per cent more likely to die after surgery.the study of available data also found lower rates of potentially life-saving surgeries, such as caesarean sections and kidney transplants, as well as quality of life surgeries, like knee replacement, for indigenous people.last summer, the canadian institute for health information published proposed standards for the collection of race-based and indigenous identity data in health care. they also flagged the potential to inflict harm in doing so, and suggested strategies to mitigate that risk, like rigorous training for those collecting the data and setting out a clear purpose for its collection and use.none of the five ottawa hospitals this newspaper spoke to was regularly collecting data from patients about their race or ethnicity, but there are indications that could change.

advertisement

at cheo, for instance, edi steering committee co-chair dr. sharon whiting said the collection of race-based data is something they will be looking at.cheo announced in february the launch of the 20-member committee, comprised of staff, volunteers and youth/family advisors across the hospital, research institute and the cheo foundation. whiting said the committee is developing working groups, one of which will be focused on data collection.asked if she would like to see cheo collect data on wait times, for example, and look at how to address potential disparities based on race or another sociodemographic factor, whiting said they hadn’t discussed gathering such data just yet, but thinks it’s a natural progression of their work.“and then you have to be prepared. if the data does reflect that there are some concerns, what are we going to do about it?“so i don’t think you would want to embark on what could be a very difficult, sensitive issue unless you’re prepared to say — well, look, if the data shows that there’s something there, that we need to address it.”some hospitals outside of ottawa have already been collecting data about patients’ race or ethnicity, and it has been used to try to better care for them.in 2012, the toronto central lhin mandated its 17 hospitals to start collecting demographic data from patients using eight questions, including one about race/ethnicity, developed through a previous hospital-led research project.a 2019 report on the data collection initiative noted that the holland bloorview kids rehabilitation hospital found “significant effect” between race/ethnicity and missed care opportunities, and brought in a transportation program in certain areas to try to address the issue.nyangweso encouraged hospitals to recognize information that has already been shared anecdotally is also a form of data into which they can tap.“centring the voices of the people that have been saying for decades, ‘this is a problem.’ saying for decades that there is racism, that there is inequity, that there is … ableism in health care, and then bringing those folks in and using that as the starting point, because we know that we can’t wait for 10 years of data to be collected in order for us to act.”berak hussain knows something about speaking up on racism in health care.the 41-year-old psychotherapist was recovering in hospital earlier this year from a severe case of covid-19. hussain, who is muslim, was on her bed, hijab draped over her arms, in the act of prayer, when a doctor entered the room and told hussain she needed to check her. as hussain detailed in an online article she penned afterwards, she didn’t respond — but the doctor, who later acknowledged to hussain she knew she was praying, said she didn’t have time to wait, put her stethoscope on hussain and started poking her. she proceeded to ask if hussain had had a bowel movement or diarrhea. after finishing her prayer, hussain confronted the doctor, who did not offer an apology, at any point, that hussain felt was genuine. she has continued to speak out since — on public platforms, and by bringing the episode to the attention of the hospital.

advertisement

when she told friends who are also medical professionals about her experience, hussain said they were livid.“and because they work in the field, they also see racism. they see this type of bigotry. and they said, ‘berak, you don’t let this go. and you speak up about it, because this woman has done this to other people. people like her need to be disciplined and not in the profession doing what they’re doing because this is unprofessional.’”the hospital reviewed the incident, and recently informed hussain discipline had been meted out and the doctor had apologized and admitted the incident shouldn’t have happened. hussain’s case was also used anonymously during cultural sensitivity training for physicians at the hospital (which the doctor in question will be taking).all in all, it’s a result hussain is pleased with.“i think a lot of positive came out of this negative situation in the end,” said hussain. “but had i not pursued it, then i would have feeling horrible and undignified and all of those feelings that i felt in that moment would have just kept replaying.”it’s critical, said bailey, of the black health alliance, that hospitals build a roadmap that can help them measure whether or not the change people are advocating for — and that hospital leaders think is important — is actually happening.“data collection in and of itself doesn’t move the dial. reporting on that data doesn’t itself move the dial. talking to people through advisory committees in and of itself doesn’t move the dial,” said bailey.but if hospitals start to combine those actions and publicly report and set targets and timelines for themselves, within the framework of a measurable strategy that somebody is responsible for driving, he said they’re more likely to see the kind of changes that are needed, when it comes to improved patient outcomes and staff working environments.at toh, the co-chairs of the hospital’s new diversity and inclusion council — one of whom is alie — want to have completed consultations by the fall with staff, patients, and organizations they work with, to identify issues that they see and incorporate this into an action plan for implementation in the new year.they’re looking to have metrics associated with everything they’re planning do, said alie. already, though, she feels they’re creating something she described as invaluable — an environment where people feel increasingly comfortable speaking up.“when people are aware that the organization actually cares and is working towards something, then … people who historically would never have said anything for fear of retribution or not being heard are now starting to have the hope that they might be heard.“and that — that is a huge step in and of itself.”

14 minute read

14 minute read